Is honey suitable for vegans?

Is honey suitable for vegans?

I’ve hesitated in publishing a post on this question, but it’s a subject that keeps arising, and so I here offer some thoughts on that controversial question: Is honey vegan?

The short and most obvious answer is of course an emphatic ‘no’. Honey is an animal product, and vegans do not eat or use animal products in any shape or form.

‘What’?! I hear a few disgruntled mumblings: bees are ‘animals’? Well, yes, they are living creatures, and honey is the food they make for themselves. Yes, that’s right; bees make honey for themselves. They do not make honey ‘for’ humans.  But at some point in our deepest history, people discovered that honey is not only delicious and nutritious as a valuable source of natural sweetness, but that it also has medicinal benefits; soothing sore throats and healing wounds in addition to tasting great – and is thus worth the trouble entailed in obtaining it. Honey is referenced in the Bible as a symbol of prosperity and health, and in the Quran as ‘a healing for humankind’. Classical Greece upheld the honeybee as a symbol of the Goddess Artemis, whilst the Ancient Egyptians believed honey to be the tears of their sun god, Ra; placing jars of honey in the burial tombs with other offerings to support the departed through their journey into the afterlife – its preservative qualities being such that honey discovered during excavations of the Great Pyramids was found to be still edible, 3,000 years on.

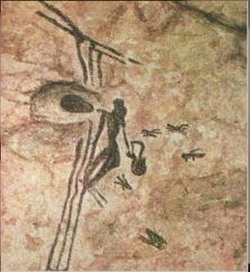

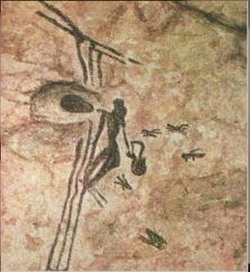

But at some point in our deepest history, people discovered that honey is not only delicious and nutritious as a valuable source of natural sweetness, but that it also has medicinal benefits; soothing sore throats and healing wounds in addition to tasting great – and is thus worth the trouble entailed in obtaining it. Honey is referenced in the Bible as a symbol of prosperity and health, and in the Quran as ‘a healing for humankind’. Classical Greece upheld the honeybee as a symbol of the Goddess Artemis, whilst the Ancient Egyptians believed honey to be the tears of their sun god, Ra; placing jars of honey in the burial tombs with other offerings to support the departed through their journey into the afterlife – its preservative qualities being such that honey discovered during excavations of the Great Pyramids was found to be still edible, 3,000 years on.  Yet Humanity’s love for honey goes back long before this, as evidenced in the ‘Man of Bicorp’ cave painting on the walls of The Cueves de la Arana (‘Spider Caves’) in Valencia, Spain, depicting honey being harvested around 8,000 years ago: not from a ‘hive’ as we know it now: people didn’t ‘keep’ bees back then but instead risked their lives for a rare taste of the sweet stuff, shimmying up trees or balancing against the cliff face on rickety rope ladders, to access the honey stored by wild colonies living high in hollow tree trunks or hard to reach caves.

Yet Humanity’s love for honey goes back long before this, as evidenced in the ‘Man of Bicorp’ cave painting on the walls of The Cueves de la Arana (‘Spider Caves’) in Valencia, Spain, depicting honey being harvested around 8,000 years ago: not from a ‘hive’ as we know it now: people didn’t ‘keep’ bees back then but instead risked their lives for a rare taste of the sweet stuff, shimmying up trees or balancing against the cliff face on rickety rope ladders, to access the honey stored by wild colonies living high in hollow tree trunks or hard to reach caves.  Wild honey harvesting continues to this day in some parts of the world, and remained the only option prior to the medieval adoption of the straw ‘Skep’ as the preferred method right through to the late 18th century, when the modern box hive began to take form. So, humans eating honey – and ‘keeping’ bees – is nothing new. But yes, honey is an animal product – and so no, technically, honey is not vegan.

Wild honey harvesting continues to this day in some parts of the world, and remained the only option prior to the medieval adoption of the straw ‘Skep’ as the preferred method right through to the late 18th century, when the modern box hive began to take form. So, humans eating honey – and ‘keeping’ bees – is nothing new. But yes, honey is an animal product – and so no, technically, honey is not vegan.  But as with many aspects of human belief and behaviour, there are many shifting shades of grey to vegan rhetoric. Many vegans I know will use no animal products at all, including honey and all related products, on the principle of not wanting to benefit from the exploitation of other living creatures. Others I know will use certain products if the animals involved are neither harmed nor exploited – such as eggs from garden-kept chickens that will not be killed for meat, and honey produced by small-scale hobby beekeepers (such as myself). I totally ‘get’ this, for I too consider the provenance of products and choose to not eat honey from large-scale producers; buying only from reputable small local beekeepers – and now, even better, endeavouring to produce my own. So yes, I understand the principles.

But as with many aspects of human belief and behaviour, there are many shifting shades of grey to vegan rhetoric. Many vegans I know will use no animal products at all, including honey and all related products, on the principle of not wanting to benefit from the exploitation of other living creatures. Others I know will use certain products if the animals involved are neither harmed nor exploited – such as eggs from garden-kept chickens that will not be killed for meat, and honey produced by small-scale hobby beekeepers (such as myself). I totally ‘get’ this, for I too consider the provenance of products and choose to not eat honey from large-scale producers; buying only from reputable small local beekeepers – and now, even better, endeavouring to produce my own. So yes, I understand the principles.  I am however shocked by the array of misinformation and blatant propaganda circulating around the vegan community with regard to honey; what it is and how it’s produced; much of it promulgated by passionately motivated yet ill-informed enthusiasts, who very clearly have never had a conversation with an actual beekeeper – never mind taken a look inside an actual hive. I here address some of these misconceptions, in what’s turned out to be a rather long post. Bear with me, as I explore some complicated issues – ultimately leaving you to make up your own mind.

I am however shocked by the array of misinformation and blatant propaganda circulating around the vegan community with regard to honey; what it is and how it’s produced; much of it promulgated by passionately motivated yet ill-informed enthusiasts, who very clearly have never had a conversation with an actual beekeeper – never mind taken a look inside an actual hive. I here address some of these misconceptions, in what’s turned out to be a rather long post. Bear with me, as I explore some complicated issues – ultimately leaving you to make up your own mind.

(for those finding this post a little too long – and it is long! – the key points are available to read individually under the Menu Heading Is Honey Vegan?

Honey propaganda myth No1: All beekeepers kill their bees in order to harvest the honey.

A lot has changed in 8,000 years. Yes, when our prehistoric ancestors plunged their bare hands deep inside the wild bee colony to break off chunks of dripping honeycomb, certainly a number of bees died in the process; mainly the larvae and grubs encased in the hexagonal cells of the comb, all of which got eaten along with the honey – valuable extra protein with the sweet hit!  Likewise, the medieval monks housing wild-caught swarms in their new-fangled straw skeps had just the one option when it came to harvesting; splitting open the skep to break up the comb to retrieve the honey (filtering out the bits of bees, larva and wax through a fine fabric sieve) before starting all over again with a new swarm in a new skep. The development of the modern box hive changed all this, with the deliberate design of a two tier system, in which the queen and colony live safely in the lower chamber, called the ‘brood box’, whilst the honey is harvested only from the level above this, called the ‘super’.

Likewise, the medieval monks housing wild-caught swarms in their new-fangled straw skeps had just the one option when it came to harvesting; splitting open the skep to break up the comb to retrieve the honey (filtering out the bits of bees, larva and wax through a fine fabric sieve) before starting all over again with a new swarm in a new skep. The development of the modern box hive changed all this, with the deliberate design of a two tier system, in which the queen and colony live safely in the lower chamber, called the ‘brood box’, whilst the honey is harvested only from the level above this, called the ‘super’.  It is a relatively easy process to lift off the supers to remove the honey without damaging or killing any bees along the way. As a small-scale hobby beekeeper, the last thing I want to do is harm my bees. A brand new colony of honey bees from a reputable breeder costs on average between £150-£200. Or you can raise your own, with time and skill. As beekeepers we spend all year nurturing and tending our bees – expending vast amounts of time, money, and effort in keeping them alive. It would be utter madness to kill them during the all-to-brief summer honey harvest – only to then have to start all over again; buying more bees! It is however a miserable fact of large-scale honey production that industrial beekeepers do not share the same regard for their bees, and may indeed find it more cost-effective to destroy the bees during or after summer honey harvest and buy more the following spring – rather than worry about (and spend time and money on) keeping them alive over the winter months. For a small-scale beekeeper, however, the exact opposite is true; we strive to support our bees to survive, and take care not to harm them.

It is a relatively easy process to lift off the supers to remove the honey without damaging or killing any bees along the way. As a small-scale hobby beekeeper, the last thing I want to do is harm my bees. A brand new colony of honey bees from a reputable breeder costs on average between £150-£200. Or you can raise your own, with time and skill. As beekeepers we spend all year nurturing and tending our bees – expending vast amounts of time, money, and effort in keeping them alive. It would be utter madness to kill them during the all-to-brief summer honey harvest – only to then have to start all over again; buying more bees! It is however a miserable fact of large-scale honey production that industrial beekeepers do not share the same regard for their bees, and may indeed find it more cost-effective to destroy the bees during or after summer honey harvest and buy more the following spring – rather than worry about (and spend time and money on) keeping them alive over the winter months. For a small-scale beekeeper, however, the exact opposite is true; we strive to support our bees to survive, and take care not to harm them.

Vegan propaganda myth No2: The Queen bee is kept prisoner by having her wings ‘ripped out’ so she cannot escape. Because bees will not produce honey without a queen.

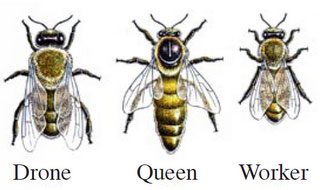

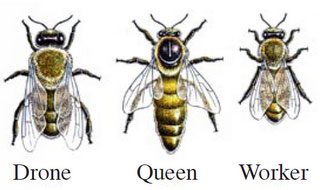

I’ve read this on numerous vegan blogs. It is not entirely true. But not entirely untrue either. Yes, some beekeepers (particularly those working on a larger scale) will prevent the queen bee from being able to fly by clipping her wings. NOT by ‘ripping’ them out but, more accurately, by trimming the wings with small sharp scissors (removing no more than a third) so they remain intact but become non-functional. Yes, I know this sounds harsh, and to understand the rational you need to first understand some basic bee behaviour.  A honeybee colony comprises three types of bee; female Queen, female workers, and male drones. The queen bee is the central figure in the colony. While there are many tens of thousands of workers and a much smaller number of male drones, there is only one Queen, and her sole purpose in life is to lay eggs – up to 2,000 per day! No queen = no bees (which of course means no honey). The queen bee’s highly specialised anatomy means she is unable to forage for her own food, or perform any of the many basic tasks of survival. She is totally dependent on her worker offspring – as they in turn are dependant on her. lf, however, she ‘fails’ in her egg-laying duties (through ill health, poor genetics or simply old age) then the colony will waste no time in raising a replacement, and they will then kill the old queen (their own mother) – making way for the new one to take over.

A honeybee colony comprises three types of bee; female Queen, female workers, and male drones. The queen bee is the central figure in the colony. While there are many tens of thousands of workers and a much smaller number of male drones, there is only one Queen, and her sole purpose in life is to lay eggs – up to 2,000 per day! No queen = no bees (which of course means no honey). The queen bee’s highly specialised anatomy means she is unable to forage for her own food, or perform any of the many basic tasks of survival. She is totally dependent on her worker offspring – as they in turn are dependant on her. lf, however, she ‘fails’ in her egg-laying duties (through ill health, poor genetics or simply old age) then the colony will waste no time in raising a replacement, and they will then kill the old queen (their own mother) – making way for the new one to take over.  Either that or they will swarm. This means that the colony will split; first they will go through that same process, raising a new queen; half will then leave with the old queen to set up home elsewhere, while the other half remain with the new queen, and carry on as they were. This leaves both halves of the split temporarily weakened and vulnerable – which can be bad news for a beekeeper, as the remaining colony may then collapse, or take time to recover from the swarming process – time that could have been better spent thriving and producing honey. But here’s the thing; if the queen cannot fly, then the colony will not swarm. That is why beekeepers clip (not rip!) the queens wings. Not to ‘keep her prisoner’ but to ensure the colony stays strong. On a personal note, I do not clip my Queen bee’s wings. In fact I don’t know any beekeepers who do. It is mainly the larger scale industrialised honey producers who do this.

Either that or they will swarm. This means that the colony will split; first they will go through that same process, raising a new queen; half will then leave with the old queen to set up home elsewhere, while the other half remain with the new queen, and carry on as they were. This leaves both halves of the split temporarily weakened and vulnerable – which can be bad news for a beekeeper, as the remaining colony may then collapse, or take time to recover from the swarming process – time that could have been better spent thriving and producing honey. But here’s the thing; if the queen cannot fly, then the colony will not swarm. That is why beekeepers clip (not rip!) the queens wings. Not to ‘keep her prisoner’ but to ensure the colony stays strong. On a personal note, I do not clip my Queen bee’s wings. In fact I don’t know any beekeepers who do. It is mainly the larger scale industrialised honey producers who do this.

Vegan Propaganda myth No3: The Queen bee is artificially inseminated against her will, and forced into servitude.

Again, this is a complicated one. Beekeepers replicate the social structure of bees in the wild. So to understand the principles and practices of modern beekeeping, it helps to first understand some basics of natural bee behaviour. A colony of honey bees is made up of one Queen and a varying number of workers and drones; a new swarm will contain around 20,000 bees in total, while a well established colony will comprise up to 60,000 – reducing down as winter approaches; increasing through spring and summer. Of this total only a few hundred will be male drones – their sole purpose being to go out and mate with a queen. The rest of the colony is made up of infertile female worker bees – and, as the name suggests, these girls do all the work, being allocated different tasks throughout the course of their lives, ranging from nursery duty (feeding and cleaning up after the babies) to door-guard, housekeeper and food production, and of course the important duty of attending to the Queen, whose only purpose in life is to lay eggs. Within her first week of life, the new Virgin Queen will leave the hive on her ‘maiden flight’, seeking out a crowd of male drones flying en-mass in search of available queens.  Only a few ‘lucky’ drones actually ever get to ‘do the deed’ – a brief encounter that leaves their genitals ripped from their body and embedded temprarily inside the queen – shortly after which, he dies. Yup: nature is brutal. The mated queen then returns to the hive, and settles down to the important work of laying eggs, day in, day out – for her entire life. A queen may have mated with several drones on that one occasion. Those drones may be infected with any of the many diseases currently contributing to bee decline; they may be carrying virus or bacterial infection (which then gets passed onto the colony, who then spread it to other colonies) or be genetically prone to certain health problems and behavioural tendencies. For this reason some beekeepers – particularly those working on a larger scale – prefer to buy in queens that have been artificially inseminated by drones bred specifically to be good tempered and disease-free – as opposed to allowing their queens to fly off and mate randomly with bees of unknown genetic profile and potential health risk. In the wild a colony will periodically raise a new queen to replace the old, in an attempt to eradicate disease and other problems, or when the Queen becomes too old to continue laying. Beekeepers simply replicate this natural behaviour, utilising the wonders of modern science. But not all beekeepers. As a small-scale hobbyist, I allow my colonies to raise their own queens – as and when they decide they need – and allow these queens to do their natural thing, flying off to mate where, and with whom, they choose. This of course brings it’s own complications; the queen may not return – or she may return un-mated and unable to lay the essential fertilised eggs; thus the colony may die (unless they are quick to raise another new queen who then successfully mates). Or she may return, carrying disease infection. For this reason, as responsible beekeepers we regularly inspect the hive and colony within, looking for signs of disease and other issues – for which we then take the necessary action, supporting the bees to overcome the problem.

Only a few ‘lucky’ drones actually ever get to ‘do the deed’ – a brief encounter that leaves their genitals ripped from their body and embedded temprarily inside the queen – shortly after which, he dies. Yup: nature is brutal. The mated queen then returns to the hive, and settles down to the important work of laying eggs, day in, day out – for her entire life. A queen may have mated with several drones on that one occasion. Those drones may be infected with any of the many diseases currently contributing to bee decline; they may be carrying virus or bacterial infection (which then gets passed onto the colony, who then spread it to other colonies) or be genetically prone to certain health problems and behavioural tendencies. For this reason some beekeepers – particularly those working on a larger scale – prefer to buy in queens that have been artificially inseminated by drones bred specifically to be good tempered and disease-free – as opposed to allowing their queens to fly off and mate randomly with bees of unknown genetic profile and potential health risk. In the wild a colony will periodically raise a new queen to replace the old, in an attempt to eradicate disease and other problems, or when the Queen becomes too old to continue laying. Beekeepers simply replicate this natural behaviour, utilising the wonders of modern science. But not all beekeepers. As a small-scale hobbyist, I allow my colonies to raise their own queens – as and when they decide they need – and allow these queens to do their natural thing, flying off to mate where, and with whom, they choose. This of course brings it’s own complications; the queen may not return – or she may return un-mated and unable to lay the essential fertilised eggs; thus the colony may die (unless they are quick to raise another new queen who then successfully mates). Or she may return, carrying disease infection. For this reason, as responsible beekeepers we regularly inspect the hive and colony within, looking for signs of disease and other issues – for which we then take the necessary action, supporting the bees to overcome the problem.

Vegan Propaganda Myth No4: Beekeepers ‘gas’ their bees into submission using smoke.

The worse example I’ve seen of this particular nugget of mis-information is in a video produced by a wildly popular young female vegan vlogger, drawing parallels between beekeeping and a Nazi concentration camp; cross-flashing images of beekeepers smoking bees with historic footage of Jews entering the gas chambers, in a video deliberately intended to enrage.  I have to say without doubt this is total rubbish; a propagandist fantasy postulated on a glaring lack of any real knowledge or experience of actual beekeeping. The reality of the bee smoker is that, again, all we are doing is replicating the bees own natural behaviour. In the wild, bees have a natural survival instinct against fire. Alerted by the smell of smoke, a colony of bees will prepare to leave their home, and instinctively they ‘pack up’ the one thing they need to survive – food. Gorging on their honey stores until their honey stomachs are full, the sudden rush of sugar makes them peaceful and drowsy. As beekeepers we utilise this natural behaviour, calming the bees with a few gently puffs of smoke, in preparation for opening the hive – making the whole experience more enjoyable for all involved – also lessening the risk of being stung. The bees are not harmed, and the beekeeper is protected: win-win.

I have to say without doubt this is total rubbish; a propagandist fantasy postulated on a glaring lack of any real knowledge or experience of actual beekeeping. The reality of the bee smoker is that, again, all we are doing is replicating the bees own natural behaviour. In the wild, bees have a natural survival instinct against fire. Alerted by the smell of smoke, a colony of bees will prepare to leave their home, and instinctively they ‘pack up’ the one thing they need to survive – food. Gorging on their honey stores until their honey stomachs are full, the sudden rush of sugar makes them peaceful and drowsy. As beekeepers we utilise this natural behaviour, calming the bees with a few gently puffs of smoke, in preparation for opening the hive – making the whole experience more enjoyable for all involved – also lessening the risk of being stung. The bees are not harmed, and the beekeeper is protected: win-win.

Vegan Propaganda Myth No5: Honey is bee vomit.

This one is high up there on the list of ‘scare tactics’ designed to put people off eating honey. And I’ll admit, it does have the ‘eugh’ factor. But it depends what you mean by ‘vomit’. If, as a human, you came staggering home late after a night on the booze, stopping off for a kebab along the way – and as you stumbled in through the door barfed up the alcohol-soaked-semi-digested contents of your stomach, this would be vomit, and not something that you would want to 1) share with your friends, or 2) shovel into a storage container to save for later.  If, however, you were a honey bee, you would have two stomachs. Yes, that’s right, and a fairly major point that these vegan propaganda bloggers somehow ‘forget’ to mention. Honey bees have two stomachs. One is the ‘true’ stomach; part of their digestive system. The other is a purpose-specific and much larger ‘honey stomach’. Not a part of the digestive system, but a separate organ entirely, serving as shopping bag, mixing bowl, cooking pot and storage container all in one, where nectar (a sweet sticky liquid collected from flowers) is stored and processed into honey before being packed for storage in the hexagonal comb cells – from where it can later be retrieved as needed. Yes, it is enzymes in the honey stomach that transform the nectar into honey. And yes, the process involves passing the nectar/honey from bee to bee, each taking a turn in the work – but hey, this is bees, not humans. And not ‘vomit’.

If, however, you were a honey bee, you would have two stomachs. Yes, that’s right, and a fairly major point that these vegan propaganda bloggers somehow ‘forget’ to mention. Honey bees have two stomachs. One is the ‘true’ stomach; part of their digestive system. The other is a purpose-specific and much larger ‘honey stomach’. Not a part of the digestive system, but a separate organ entirely, serving as shopping bag, mixing bowl, cooking pot and storage container all in one, where nectar (a sweet sticky liquid collected from flowers) is stored and processed into honey before being packed for storage in the hexagonal comb cells – from where it can later be retrieved as needed. Yes, it is enzymes in the honey stomach that transform the nectar into honey. And yes, the process involves passing the nectar/honey from bee to bee, each taking a turn in the work – but hey, this is bees, not humans. And not ‘vomit’.

Vegan propaganda myth No6: beekeepers ‘steal’ honey from bees, and feed them instead on white sugar, which is bad for their health.

Again, the answer lies somewhere between yes and no. Honey is a specialised food, made by bees for bees. No getting away from that fact. And so yes, in taking the honey from a beehive we are, in effect, ‘stealing’ the food that the bees have worked so hard to make for themselves.  Bees need two main foods to survive, and both are collected from flowers; protein (in the form of pollen) and carbohydrate (in the form of sugar). Honey is 82% sugar, but it also contains trace vitamins and minerals and mystery substances that science is unable to identify or replicate. It really is magical stuff, and as a responsible beekeeper putting the welfare of my bees before my own sweet tooth, I personally choose to leave sufficient honey on the hive for the bees, taking only the surplus – if there is a surplus – for human use. But of course, not everyone does it this way, and again it is commercial beekeepers who are most guilty of ‘stealing’ the entire honey harvest from bees that they may then destroy – or, if they do keep them going overwinter, feed on sugar as the cheaper alternative. The beekeeping community is strongly divided over whether this does – or does not – harm the bees health. I personally feel that it’s a bit of a ‘no brainer’. Bees invest their entire life in making this special food, on which they rely for survival. I myself believe that replacing this purpose-created food with processed white sugar has got to have a negative impact on bee health. It is a fact, however, that all beekeepers will at some point rely on sugar as a means of ensuring their bees have enough to eat in times of shortage. Bad weather, extreme cold, attack by predators, disease and other disasters can leave a colony short of food; as can an increase in brood (baby bee) production; and the only way to overcome this is to provide additional sustenance, in the form of sugar as carbohydrate. This is done by giving Syrup, fondant or bee-candy, which are made by dissolving and/or cooking sugar and water in variable combination. My own syrup and candy recipes include the addition of herbs (lavender, thyme, rosemary) for medicinal effect, and I give these processed white sugar products only to supplement – not replace – the bees own honey.

Bees need two main foods to survive, and both are collected from flowers; protein (in the form of pollen) and carbohydrate (in the form of sugar). Honey is 82% sugar, but it also contains trace vitamins and minerals and mystery substances that science is unable to identify or replicate. It really is magical stuff, and as a responsible beekeeper putting the welfare of my bees before my own sweet tooth, I personally choose to leave sufficient honey on the hive for the bees, taking only the surplus – if there is a surplus – for human use. But of course, not everyone does it this way, and again it is commercial beekeepers who are most guilty of ‘stealing’ the entire honey harvest from bees that they may then destroy – or, if they do keep them going overwinter, feed on sugar as the cheaper alternative. The beekeeping community is strongly divided over whether this does – or does not – harm the bees health. I personally feel that it’s a bit of a ‘no brainer’. Bees invest their entire life in making this special food, on which they rely for survival. I myself believe that replacing this purpose-created food with processed white sugar has got to have a negative impact on bee health. It is a fact, however, that all beekeepers will at some point rely on sugar as a means of ensuring their bees have enough to eat in times of shortage. Bad weather, extreme cold, attack by predators, disease and other disasters can leave a colony short of food; as can an increase in brood (baby bee) production; and the only way to overcome this is to provide additional sustenance, in the form of sugar as carbohydrate. This is done by giving Syrup, fondant or bee-candy, which are made by dissolving and/or cooking sugar and water in variable combination. My own syrup and candy recipes include the addition of herbs (lavender, thyme, rosemary) for medicinal effect, and I give these processed white sugar products only to supplement – not replace – the bees own honey.

Vegan Propaganda Myth No7: by not eating honey you will ‘save’ the honeybee.

This is a difficult one. It is a fact that honey bees are in decline, at an alarming rate. Not just those ‘enslaved’ by beekeepers but bees in the wild as well. There are ten or so diseases potentially fatal to honeybees.  These diseases spread from bee to bee, and from colony to colony, through the normal social contact of bees going about their normal bee activity – unknowingly passing virus, bacteria, fungus, moulds and parasites between themselves and each other. As beekeepers we regularly inspect our hives for signs of these problems, and take the appropriate action to prevent or treat. Wild bees simply die from these same diseases, or at best struggle against adversity – in the meantime spreading the infections far and wide, free from human ‘interference’. From this perspective, domestic beekeeping plays a vital role in supporting honey bees to survive and thrive; beekeepers striving to protect and strengthen bee colonies against disease. Again, this is more true of small-scale beekeepers, rather than those working on an industrial scale; for as hobbyists and small-scale producers we take care to protect and maintain the health of our bees – whereas larger scale operators may be more inclined to miss the signs, with such vast populations to monitor, and may prefer to destroy rather than treat, if disease is present. They also work within a much more generous financial margin; the loss of one hive countered by the profits of another. Whereas small independent beekeepers will be working within a much tighter financial framework, reaping smaller monetary rewards whilst very likely paying out more in higher quality bee care. So, not eating honey will not ‘save’ the bees and could in fact have the total opposite effect; forcing the more responsible and environmentally aware beekeeper out of action, thus reducing the total bee population, with the resultant drop in monitoring and treatment leaving bee disease free to spread more freely.

These diseases spread from bee to bee, and from colony to colony, through the normal social contact of bees going about their normal bee activity – unknowingly passing virus, bacteria, fungus, moulds and parasites between themselves and each other. As beekeepers we regularly inspect our hives for signs of these problems, and take the appropriate action to prevent or treat. Wild bees simply die from these same diseases, or at best struggle against adversity – in the meantime spreading the infections far and wide, free from human ‘interference’. From this perspective, domestic beekeeping plays a vital role in supporting honey bees to survive and thrive; beekeepers striving to protect and strengthen bee colonies against disease. Again, this is more true of small-scale beekeepers, rather than those working on an industrial scale; for as hobbyists and small-scale producers we take care to protect and maintain the health of our bees – whereas larger scale operators may be more inclined to miss the signs, with such vast populations to monitor, and may prefer to destroy rather than treat, if disease is present. They also work within a much more generous financial margin; the loss of one hive countered by the profits of another. Whereas small independent beekeepers will be working within a much tighter financial framework, reaping smaller monetary rewards whilst very likely paying out more in higher quality bee care. So, not eating honey will not ‘save’ the bees and could in fact have the total opposite effect; forcing the more responsible and environmentally aware beekeeper out of action, thus reducing the total bee population, with the resultant drop in monitoring and treatment leaving bee disease free to spread more freely.

One argument against this, is that bees in the wild ‘will find a way’ – the assumption being that their immune system will adapt to overcome the problem. Well, yes and no. In an ideal world, wild bees would be thriving, their immune systems and overall health bolstered by the array of nutrients found in natural forage. But the truth is that natural bee habitat, including food-forage, has dramatically declined and continues to do so, meaning that bees – and other pollinator insects – simply do not have enough to eat, and what they do eat may be lacking in sufficient nutrients and/or contaminated by the chemical fertilisers and herbicides of industrial agriculture – the very same industrial agriculture that produces the fruit and vegetables eaten by vegans. So you could argue, in reverse, that if you don’t eat honey but you DO eat fruit and vegetables, as a vegan you are yourself contributing to harming – rather than ‘saving’ – the bees!

Yes, I’ll say that again. By eating fruit and vegetables (including nuts and seeds) you are benefiting from the work of honey bees – including those that are commercially managed. The very same bees whose honey you may refuse to eat.

Let me explain.

The vast scale of industrial farming, and the absence of wild habitat, means there are simply not enough wild bees and other insects available to pollinate the huge fields of mono-crop agriculture.  In the absence of sufficient wild insects it is normal practice for large-scale farmers to employ commercial beekeepers, transporting thousands of hives across thousands of miles to different locations at different times of the year, to pollinate these crops into production. Almonds, for example (the key ingredient in that vegan staple; almond milk) rely on commercial bee pollination – as do so many of the foods central to a vegan lifestyle (avocados, for example). Indeed, if you as a vegan want to truly avoid consuming products reliant on the commercial exploitation of honeybees, then your only option would be a greatly restricted diet; mainly grass-based cereal crops (wheat, oats, barley, etc), wind-pollinated plants (tomatoes – hoorah!) and non-pollinated crops (potatoes, for example). Not much fun. And not much help to the bees and other insects, nor your own health – or the environment as a whole.

In the absence of sufficient wild insects it is normal practice for large-scale farmers to employ commercial beekeepers, transporting thousands of hives across thousands of miles to different locations at different times of the year, to pollinate these crops into production. Almonds, for example (the key ingredient in that vegan staple; almond milk) rely on commercial bee pollination – as do so many of the foods central to a vegan lifestyle (avocados, for example). Indeed, if you as a vegan want to truly avoid consuming products reliant on the commercial exploitation of honeybees, then your only option would be a greatly restricted diet; mainly grass-based cereal crops (wheat, oats, barley, etc), wind-pollinated plants (tomatoes – hoorah!) and non-pollinated crops (potatoes, for example). Not much fun. And not much help to the bees and other insects, nor your own health – or the environment as a whole.  There is however a better way, and that is to buy only local and/or organic produce from small independent producers or, even better, grow your own (thus reducing the toxic load of agricultural chemicals). You could also grow pollinator-friendly flowers to feed and strengthen your local bee (and other pollinator insect) population. And you could also (here comes the curveball!) support your local small-scale beekeeper by … buying and eating their honey!

There is however a better way, and that is to buy only local and/or organic produce from small independent producers or, even better, grow your own (thus reducing the toxic load of agricultural chemicals). You could also grow pollinator-friendly flowers to feed and strengthen your local bee (and other pollinator insect) population. And you could also (here comes the curveball!) support your local small-scale beekeeper by … buying and eating their honey!

Well, haven’t I just lobbed a grenade there?! Please bear with me, just a moment more. Technically, no, honey is not vegan.  All honeys, however, are not created equal. Where the large-scale commercial beekeeper (working alongside the large scale commercial farmer) is concerned primarily with financial profit, the small-scale local beekeeper is first and foremost concerned with the welfare of their bees. Many small-scale beekeepers are also enthusiastic gardeners or allotment growers, supporting their local environment to support its local bee (and other pollinator insect) population. Buying and enjoying honey from your local small scale beekeeper actively supports that beekeeper in their endeavours. So yes, while honey – being an animal product – is technically not vegan, it very much depends on the honey, and where you – as a vegan – sit on the sliding scale of veganism. If your blanket rule is ‘no animal products, per se’ then no, you will quite rightly choose not to eat honey. But if your main concern is the ethics and morality of beekeeping practice and the welfare of honeybees, and you want to support the natural environment as a wider whole, then honey from a small local beekeeper could be for you. It is ultimately a matter of personal choice – but a choice that is better made on the basis of accurate information, as opposed to sensationalist propaganda.

All honeys, however, are not created equal. Where the large-scale commercial beekeeper (working alongside the large scale commercial farmer) is concerned primarily with financial profit, the small-scale local beekeeper is first and foremost concerned with the welfare of their bees. Many small-scale beekeepers are also enthusiastic gardeners or allotment growers, supporting their local environment to support its local bee (and other pollinator insect) population. Buying and enjoying honey from your local small scale beekeeper actively supports that beekeeper in their endeavours. So yes, while honey – being an animal product – is technically not vegan, it very much depends on the honey, and where you – as a vegan – sit on the sliding scale of veganism. If your blanket rule is ‘no animal products, per se’ then no, you will quite rightly choose not to eat honey. But if your main concern is the ethics and morality of beekeeping practice and the welfare of honeybees, and you want to support the natural environment as a wider whole, then honey from a small local beekeeper could be for you. It is ultimately a matter of personal choice – but a choice that is better made on the basis of accurate information, as opposed to sensationalist propaganda.

Ok, so I tried to come up with a clever and witty title for this one – and failed. Chutney. Not a word that lends itself easily to rhyme or humour, but a classic addition to the traditional Ploughman’s Lunch; a go-to accompaniment to cold meats and cheese, and an ideal way to preserve allotment fruit and veg. And OH so typically English, right? Well, yeah-but-no-but. As a savoury preserve made from fruit and veg simmered with sugar, vinegar and spices, chutney has it’s origins in British Colonialism. Yup; as with so many aspects of this small island’s insular culture (think tea, marmalade, and Chicken Tikka Masala) chutney is an idea adapted from elsewhere; the sugar and spices a legacy of British Empire expansion, and the word itself rooted in the Hindi चटनी chaṭnī, meaning ‘to lick’.

Ok, so I tried to come up with a clever and witty title for this one – and failed. Chutney. Not a word that lends itself easily to rhyme or humour, but a classic addition to the traditional Ploughman’s Lunch; a go-to accompaniment to cold meats and cheese, and an ideal way to preserve allotment fruit and veg. And OH so typically English, right? Well, yeah-but-no-but. As a savoury preserve made from fruit and veg simmered with sugar, vinegar and spices, chutney has it’s origins in British Colonialism. Yup; as with so many aspects of this small island’s insular culture (think tea, marmalade, and Chicken Tikka Masala) chutney is an idea adapted from elsewhere; the sugar and spices a legacy of British Empire expansion, and the word itself rooted in the Hindi चटनी chaṭnī, meaning ‘to lick’. ![IMG_20170717_130359[1]](https://somewhereinwestcornwall.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/img_20170717_1303591.jpg?w=302&h=227) I am not sure I’d want to be ‘licking’ chutney up all on it’s own, but it’s definitely a good thing to have stashed in the cupboard; a great way to use up allotment gluts, and something I’ve been experimenting with in recent years. Turns out chutney is easy to make, once you know the basics. Endless ingredient combinations are possible, meaning that no two batches need ever turn out the same (although they can if you want them to: just write it down so you can roll out your own signature recipe, time after time). Stored in super-clean, tightly-sealed jars, chutney will keep for aaaaages (years and years) and – bonus – gets better with age.

I am not sure I’d want to be ‘licking’ chutney up all on it’s own, but it’s definitely a good thing to have stashed in the cupboard; a great way to use up allotment gluts, and something I’ve been experimenting with in recent years. Turns out chutney is easy to make, once you know the basics. Endless ingredient combinations are possible, meaning that no two batches need ever turn out the same (although they can if you want them to: just write it down so you can roll out your own signature recipe, time after time). Stored in super-clean, tightly-sealed jars, chutney will keep for aaaaages (years and years) and – bonus – gets better with age. And of course, glass jars. With twist-top metal vinegar-proof lids. You can re-use jars. And you can sometimes re-use lids; the key point is they must be vinegar-proof, not smell of whatever they’ve been used for previously, and with the plastic inner seal sufficiently intact to close properly again; the idea is to keep air out (from the finished product) preventing the growth of bacterial mould, thus enabling long-term storage. New lids cost mere pennies, and are worth investing in; rather than make do with less-than-perfect old ones. The jars will need sterilising. The easiest way is to wash them, then heat in the oven (more of this later). Or put them in the dishwasher on hottest setting. They must be absolutely clean and completely dry before the chutney goes in.

And of course, glass jars. With twist-top metal vinegar-proof lids. You can re-use jars. And you can sometimes re-use lids; the key point is they must be vinegar-proof, not smell of whatever they’ve been used for previously, and with the plastic inner seal sufficiently intact to close properly again; the idea is to keep air out (from the finished product) preventing the growth of bacterial mould, thus enabling long-term storage. New lids cost mere pennies, and are worth investing in; rather than make do with less-than-perfect old ones. The jars will need sterilising. The easiest way is to wash them, then heat in the oven (more of this later). Or put them in the dishwasher on hottest setting. They must be absolutely clean and completely dry before the chutney goes in. Wash and rinse your jars, and also if they need it, the lids. Put jars into oven ready to sterilise – keep the oven at this point switched off. (or sterilise in dishwasher, whichever you prefer). The lids also need to be be completely clean and totally dry. Do not, however, attempt to sterilise them in the oven at the same time as the jars; this will only melt the plastic seal, rendering them useless.

Wash and rinse your jars, and also if they need it, the lids. Put jars into oven ready to sterilise – keep the oven at this point switched off. (or sterilise in dishwasher, whichever you prefer). The lids also need to be be completely clean and totally dry. Do not, however, attempt to sterilise them in the oven at the same time as the jars; this will only melt the plastic seal, rendering them useless.

The chutney should not touch the lid, but you do want as narrow a gap as possible, between the two (keeping the air space minimal, for bacteria and mould control). And take your time; smaller rather than larger spoonfuls, to avoid trapping too much air as bubbles in the finished product. Use a wide-neck funnel to avoid spilling chutney down the outside of jars. Tap each filled jar gently but firmly a few times on the worktop, to level the surface and allow air to rise and escape.

The chutney should not touch the lid, but you do want as narrow a gap as possible, between the two (keeping the air space minimal, for bacteria and mould control). And take your time; smaller rather than larger spoonfuls, to avoid trapping too much air as bubbles in the finished product. Use a wide-neck funnel to avoid spilling chutney down the outside of jars. Tap each filled jar gently but firmly a few times on the worktop, to level the surface and allow air to rise and escape. Experiment and have fun. Add to your stash and, every now and then – over the coming weeks, months, years – open the cupboard and admire your glistening jars, and feel pleased with yourself; you are the Chutney King / Queen.

Experiment and have fun. Add to your stash and, every now and then – over the coming weeks, months, years – open the cupboard and admire your glistening jars, and feel pleased with yourself; you are the Chutney King / Queen. ‘Ah yes’ the smiling Customer Services assistant replied: ‘You need to have your details added to the list, and then just wait – we’ll phone you; there’s a waiting list; you’ll be number five ….’.

‘Ah yes’ the smiling Customer Services assistant replied: ‘You need to have your details added to the list, and then just wait – we’ll phone you; there’s a waiting list; you’ll be number five ….’. In such a short space of time – and with several others between me in receipt of the same – there is evidently a LOT of sugar getting spilled or simply becoming unsalable due to broken packaging. So top marks to Tesco for putting this scheme into action in collaboration with

In such a short space of time – and with several others between me in receipt of the same – there is evidently a LOT of sugar getting spilled or simply becoming unsalable due to broken packaging. So top marks to Tesco for putting this scheme into action in collaboration with  This lot, I discovered, must have been swept up from (I’m guessing) the bakery floor, for I found it to be riddled with flakes of (I think) pastry (or was it nuts??) … Not that this mattered, for it was no great effort to shake the whole lot through a sieve, filtering out the detritus to be left with a fine mound of perfectly usable (for bee purposes) sugar – ideal for transforming into bee syrup, which I’ve been regularly making to feed to my bees

This lot, I discovered, must have been swept up from (I’m guessing) the bakery floor, for I found it to be riddled with flakes of (I think) pastry (or was it nuts??) … Not that this mattered, for it was no great effort to shake the whole lot through a sieve, filtering out the detritus to be left with a fine mound of perfectly usable (for bee purposes) sugar – ideal for transforming into bee syrup, which I’ve been regularly making to feed to my bees  since around the start of September. A simple solution of sugar dissolved in hot water, allowed to cool and then stored in large plastic bottles. Easy to transport and ideal for pouring to fill the purpose-designed feeder that goes into the top of the hive, beneath the roof, where the bees very quickly get stuck in – enjoying the easily-assimilated carbohydrate as a much needed energy boost at this busy time, preparing to hunker down for winter.

since around the start of September. A simple solution of sugar dissolved in hot water, allowed to cool and then stored in large plastic bottles. Easy to transport and ideal for pouring to fill the purpose-designed feeder that goes into the top of the hive, beneath the roof, where the bees very quickly get stuck in – enjoying the easily-assimilated carbohydrate as a much needed energy boost at this busy time, preparing to hunker down for winter.  I’ve even experimented by adding dried herbs to infuse the syrup for medicinal effect – a little ‘insider tip’ from an experienced beekeeper friend, adding variable combinations of lavender, sage, thyme and rosemary – all of which I grow in my garden and store dried for kitchen use.

I’ve even experimented by adding dried herbs to infuse the syrup for medicinal effect – a little ‘insider tip’ from an experienced beekeeper friend, adding variable combinations of lavender, sage, thyme and rosemary – all of which I grow in my garden and store dried for kitchen use. It’s essential however, that we supplement in this way only when we have no forthcoming plans to take off honey, and also not when there is sufficient forage (nectar-rich flowers in bloom), because although this additional sugar is intended for immediate consumption (like a person snacking on a high-energy bar before a run) it is not unheard of for bees to store these sugar supplies in the comb, just as they do with nectar (collected from flowers) – meaning the ‘honey’ we take off could in fact be white sugar, processed by the bees in the same way. Not quite the high-quality natural product that we (or they!) are aiming for!

It’s essential however, that we supplement in this way only when we have no forthcoming plans to take off honey, and also not when there is sufficient forage (nectar-rich flowers in bloom), because although this additional sugar is intended for immediate consumption (like a person snacking on a high-energy bar before a run) it is not unheard of for bees to store these sugar supplies in the comb, just as they do with nectar (collected from flowers) – meaning the ‘honey’ we take off could in fact be white sugar, processed by the bees in the same way. Not quite the high-quality natural product that we (or they!) are aiming for!

Is honey suitable for vegans?

Is honey suitable for vegans? But at some point in our deepest history, people discovered that honey is not only delicious and nutritious as a valuable source of natural sweetness, but that it also has medicinal benefits; soothing sore throats and healing wounds in addition to tasting great – and is thus worth the trouble entailed in obtaining it. Honey is referenced in the Bible as a symbol of prosperity and health, and in the Quran as ‘a healing for humankind’. Classical Greece upheld the honeybee as a symbol of the Goddess Artemis, whilst the Ancient Egyptians believed honey to be the tears of their sun god, Ra; placing jars of honey in the burial tombs with other offerings to support the departed through their journey into the afterlife – its preservative qualities being such that honey discovered during excavations of the Great Pyramids was found to be still edible, 3,000 years on.

But at some point in our deepest history, people discovered that honey is not only delicious and nutritious as a valuable source of natural sweetness, but that it also has medicinal benefits; soothing sore throats and healing wounds in addition to tasting great – and is thus worth the trouble entailed in obtaining it. Honey is referenced in the Bible as a symbol of prosperity and health, and in the Quran as ‘a healing for humankind’. Classical Greece upheld the honeybee as a symbol of the Goddess Artemis, whilst the Ancient Egyptians believed honey to be the tears of their sun god, Ra; placing jars of honey in the burial tombs with other offerings to support the departed through their journey into the afterlife – its preservative qualities being such that honey discovered during excavations of the Great Pyramids was found to be still edible, 3,000 years on.  Yet Humanity’s love for honey goes back long before this, as evidenced in the ‘Man of Bicorp’ cave painting on the walls of The Cueves de la Arana (‘Spider Caves’) in Valencia, Spain, depicting honey being harvested around 8,000 years ago: not from a ‘hive’ as we know it now: people didn’t ‘keep’ bees back then but instead risked their lives for a rare taste of the sweet stuff, shimmying up trees or balancing against the cliff face on rickety rope ladders, to access the honey stored by wild colonies living high in hollow tree trunks or hard to reach caves.

Yet Humanity’s love for honey goes back long before this, as evidenced in the ‘Man of Bicorp’ cave painting on the walls of The Cueves de la Arana (‘Spider Caves’) in Valencia, Spain, depicting honey being harvested around 8,000 years ago: not from a ‘hive’ as we know it now: people didn’t ‘keep’ bees back then but instead risked their lives for a rare taste of the sweet stuff, shimmying up trees or balancing against the cliff face on rickety rope ladders, to access the honey stored by wild colonies living high in hollow tree trunks or hard to reach caves.  Wild honey harvesting continues to this day in some parts of the world, and remained the only option prior to the medieval adoption of the straw ‘Skep’ as the preferred method right through to the late 18th century, when the modern box hive began to take form. So, humans eating honey – and ‘keeping’ bees – is nothing new. But yes, honey is an animal product – and so no, technically, honey is not vegan.

Wild honey harvesting continues to this day in some parts of the world, and remained the only option prior to the medieval adoption of the straw ‘Skep’ as the preferred method right through to the late 18th century, when the modern box hive began to take form. So, humans eating honey – and ‘keeping’ bees – is nothing new. But yes, honey is an animal product – and so no, technically, honey is not vegan.  But as with many aspects of human belief and behaviour, there are many shifting shades of grey to vegan rhetoric. Many vegans I know will use no animal products at all, including honey and all related products, on the principle of not wanting to benefit from the exploitation of other living creatures. Others I know will use certain products if the animals involved are neither harmed nor exploited – such as eggs from garden-kept chickens that will not be killed for meat, and honey produced by small-scale hobby beekeepers (such as myself). I totally ‘get’ this, for I too consider the provenance of products and choose to not eat honey from large-scale producers; buying only from reputable small local beekeepers – and now, even better, endeavouring to produce my own. So yes, I understand the principles.

But as with many aspects of human belief and behaviour, there are many shifting shades of grey to vegan rhetoric. Many vegans I know will use no animal products at all, including honey and all related products, on the principle of not wanting to benefit from the exploitation of other living creatures. Others I know will use certain products if the animals involved are neither harmed nor exploited – such as eggs from garden-kept chickens that will not be killed for meat, and honey produced by small-scale hobby beekeepers (such as myself). I totally ‘get’ this, for I too consider the provenance of products and choose to not eat honey from large-scale producers; buying only from reputable small local beekeepers – and now, even better, endeavouring to produce my own. So yes, I understand the principles.  I am however shocked by the array of misinformation and blatant propaganda circulating around the vegan community with regard to honey; what it is and how it’s produced; much of it promulgated by passionately motivated yet ill-informed enthusiasts, who very clearly have never had a conversation with an actual beekeeper – never mind taken a look inside an actual hive. I here address some of these misconceptions, in what’s turned out to be a rather long post. Bear with me, as I explore some complicated issues – ultimately leaving you to make up your own mind.

I am however shocked by the array of misinformation and blatant propaganda circulating around the vegan community with regard to honey; what it is and how it’s produced; much of it promulgated by passionately motivated yet ill-informed enthusiasts, who very clearly have never had a conversation with an actual beekeeper – never mind taken a look inside an actual hive. I here address some of these misconceptions, in what’s turned out to be a rather long post. Bear with me, as I explore some complicated issues – ultimately leaving you to make up your own mind. Likewise, the medieval monks housing wild-caught swarms in their new-fangled straw skeps had just the one option when it came to harvesting; splitting open the skep to break up the comb to retrieve the honey (filtering out the bits of bees, larva and wax through a fine fabric sieve) before starting all over again with a new swarm in a new skep. The development of the modern box hive changed all this, with the deliberate design of a two tier system, in which the queen and colony live safely in the lower chamber, called the ‘brood box’, whilst the honey is harvested only from the level above this, called the ‘super’.

Likewise, the medieval monks housing wild-caught swarms in their new-fangled straw skeps had just the one option when it came to harvesting; splitting open the skep to break up the comb to retrieve the honey (filtering out the bits of bees, larva and wax through a fine fabric sieve) before starting all over again with a new swarm in a new skep. The development of the modern box hive changed all this, with the deliberate design of a two tier system, in which the queen and colony live safely in the lower chamber, called the ‘brood box’, whilst the honey is harvested only from the level above this, called the ‘super’.  It is a relatively easy process to lift off the supers to remove the honey without damaging or killing any bees along the way. As a small-scale hobby beekeeper, the last thing I want to do is harm my bees. A brand new colony of honey bees from a reputable breeder costs on average between £150-£200. Or you can raise your own, with time and skill. As beekeepers we spend all year nurturing and tending our bees – expending vast amounts of time, money, and effort in keeping them alive. It would be utter madness to kill them during the all-to-brief summer honey harvest – only to then have to start all over again; buying more bees! It is however a miserable fact of large-scale honey production that industrial beekeepers do not share the same regard for their bees, and may indeed find it more cost-effective to destroy the bees during or after summer honey harvest and buy more the following spring – rather than worry about (and spend time and money on) keeping them alive over the winter months. For a small-scale beekeeper, however, the exact opposite is true; we strive to support our bees to survive, and take care not to harm them.

It is a relatively easy process to lift off the supers to remove the honey without damaging or killing any bees along the way. As a small-scale hobby beekeeper, the last thing I want to do is harm my bees. A brand new colony of honey bees from a reputable breeder costs on average between £150-£200. Or you can raise your own, with time and skill. As beekeepers we spend all year nurturing and tending our bees – expending vast amounts of time, money, and effort in keeping them alive. It would be utter madness to kill them during the all-to-brief summer honey harvest – only to then have to start all over again; buying more bees! It is however a miserable fact of large-scale honey production that industrial beekeepers do not share the same regard for their bees, and may indeed find it more cost-effective to destroy the bees during or after summer honey harvest and buy more the following spring – rather than worry about (and spend time and money on) keeping them alive over the winter months. For a small-scale beekeeper, however, the exact opposite is true; we strive to support our bees to survive, and take care not to harm them. A honeybee colony comprises three types of bee; female Queen, female workers, and male drones. The queen bee is the central figure in the colony. While there are many tens of thousands of workers and a much smaller number of male drones, there is only one Queen, and her sole purpose in life is to lay eggs – up to 2,000 per day! No queen = no bees (which of course means no honey). The queen bee’s highly specialised anatomy means she is unable to forage for her own food, or perform any of the many basic tasks of survival. She is totally dependent on her worker offspring – as they in turn are dependant on her. lf, however, she ‘fails’ in her egg-laying duties (through ill health, poor genetics or simply old age) then the colony will waste no time in raising a replacement, and they will then kill the old queen (their own mother) – making way for the new one to take over.

A honeybee colony comprises three types of bee; female Queen, female workers, and male drones. The queen bee is the central figure in the colony. While there are many tens of thousands of workers and a much smaller number of male drones, there is only one Queen, and her sole purpose in life is to lay eggs – up to 2,000 per day! No queen = no bees (which of course means no honey). The queen bee’s highly specialised anatomy means she is unable to forage for her own food, or perform any of the many basic tasks of survival. She is totally dependent on her worker offspring – as they in turn are dependant on her. lf, however, she ‘fails’ in her egg-laying duties (through ill health, poor genetics or simply old age) then the colony will waste no time in raising a replacement, and they will then kill the old queen (their own mother) – making way for the new one to take over.  Either that or they will swarm. This means that the colony will split; first they will go through that same process, raising a new queen; half will then leave with the old queen to set up home elsewhere, while the other half remain with the new queen, and carry on as they were. This leaves both halves of the split temporarily weakened and vulnerable – which can be bad news for a beekeeper, as the remaining colony may then collapse, or take time to recover from the swarming process – time that could have been better spent thriving and producing honey. But here’s the thing; if the queen cannot fly, then the colony will not swarm. That is why beekeepers clip (not rip!) the queens wings. Not to ‘keep her prisoner’ but to ensure the colony stays strong. On a personal note, I do not clip my Queen bee’s wings. In fact I don’t know any beekeepers who do. It is mainly the larger scale industrialised honey producers who do this.

Either that or they will swarm. This means that the colony will split; first they will go through that same process, raising a new queen; half will then leave with the old queen to set up home elsewhere, while the other half remain with the new queen, and carry on as they were. This leaves both halves of the split temporarily weakened and vulnerable – which can be bad news for a beekeeper, as the remaining colony may then collapse, or take time to recover from the swarming process – time that could have been better spent thriving and producing honey. But here’s the thing; if the queen cannot fly, then the colony will not swarm. That is why beekeepers clip (not rip!) the queens wings. Not to ‘keep her prisoner’ but to ensure the colony stays strong. On a personal note, I do not clip my Queen bee’s wings. In fact I don’t know any beekeepers who do. It is mainly the larger scale industrialised honey producers who do this. Only a few ‘lucky’ drones actually ever get to ‘do the deed’ – a brief encounter that leaves their genitals ripped from their body and embedded temprarily inside the queen – shortly after which, he dies. Yup: nature is brutal. The mated queen then returns to the hive, and settles down to the important work of laying eggs, day in, day out – for her entire life. A queen may have mated with several drones on that one occasion. Those drones may be infected with any of the many diseases currently contributing to bee decline; they may be carrying virus or bacterial infection (which then gets passed onto the colony, who then spread it to other colonies) or be genetically prone to certain health problems and behavioural tendencies. For this reason some beekeepers – particularly those working on a larger scale – prefer to buy in queens that have been artificially inseminated by drones bred specifically to be good tempered and disease-free – as opposed to allowing their queens to fly off and mate randomly with bees of unknown genetic profile and potential health risk. In the wild a colony will periodically raise a new queen to replace the old, in an attempt to eradicate disease and other problems, or when the Queen becomes too old to continue laying. Beekeepers simply replicate this natural behaviour, utilising the wonders of modern science. But not all beekeepers. As a small-scale hobbyist, I allow my colonies to raise their own queens – as and when they decide they need – and allow these queens to do their natural thing, flying off to mate where, and with whom, they choose. This of course brings it’s own complications; the queen may not return – or she may return un-mated and unable to lay the essential fertilised eggs; thus the colony may die (unless they are quick to raise another new queen who then successfully mates). Or she may return, carrying disease infection. For this reason, as responsible beekeepers we regularly inspect the hive and colony within, looking for signs of disease and other issues – for which we then take the necessary action, supporting the bees to overcome the problem.

Only a few ‘lucky’ drones actually ever get to ‘do the deed’ – a brief encounter that leaves their genitals ripped from their body and embedded temprarily inside the queen – shortly after which, he dies. Yup: nature is brutal. The mated queen then returns to the hive, and settles down to the important work of laying eggs, day in, day out – for her entire life. A queen may have mated with several drones on that one occasion. Those drones may be infected with any of the many diseases currently contributing to bee decline; they may be carrying virus or bacterial infection (which then gets passed onto the colony, who then spread it to other colonies) or be genetically prone to certain health problems and behavioural tendencies. For this reason some beekeepers – particularly those working on a larger scale – prefer to buy in queens that have been artificially inseminated by drones bred specifically to be good tempered and disease-free – as opposed to allowing their queens to fly off and mate randomly with bees of unknown genetic profile and potential health risk. In the wild a colony will periodically raise a new queen to replace the old, in an attempt to eradicate disease and other problems, or when the Queen becomes too old to continue laying. Beekeepers simply replicate this natural behaviour, utilising the wonders of modern science. But not all beekeepers. As a small-scale hobbyist, I allow my colonies to raise their own queens – as and when they decide they need – and allow these queens to do their natural thing, flying off to mate where, and with whom, they choose. This of course brings it’s own complications; the queen may not return – or she may return un-mated and unable to lay the essential fertilised eggs; thus the colony may die (unless they are quick to raise another new queen who then successfully mates). Or she may return, carrying disease infection. For this reason, as responsible beekeepers we regularly inspect the hive and colony within, looking for signs of disease and other issues – for which we then take the necessary action, supporting the bees to overcome the problem. I have to say without doubt this is total rubbish; a propagandist fantasy postulated on a glaring lack of any real knowledge or experience of actual beekeeping. The reality of the bee smoker is that, again, all we are doing is replicating the bees own natural behaviour. In the wild, bees have a natural survival instinct against fire. Alerted by the smell of smoke, a colony of bees will prepare to leave their home, and instinctively they ‘pack up’ the one thing they need to survive – food. Gorging on their honey stores until their honey stomachs are full, the sudden rush of sugar makes them peaceful and drowsy. As beekeepers we utilise this natural behaviour, calming the bees with a few gently puffs of smoke, in preparation for opening the hive – making the whole experience more enjoyable for all involved – also lessening the risk of being stung. The bees are not harmed, and the beekeeper is protected: win-win.

I have to say without doubt this is total rubbish; a propagandist fantasy postulated on a glaring lack of any real knowledge or experience of actual beekeeping. The reality of the bee smoker is that, again, all we are doing is replicating the bees own natural behaviour. In the wild, bees have a natural survival instinct against fire. Alerted by the smell of smoke, a colony of bees will prepare to leave their home, and instinctively they ‘pack up’ the one thing they need to survive – food. Gorging on their honey stores until their honey stomachs are full, the sudden rush of sugar makes them peaceful and drowsy. As beekeepers we utilise this natural behaviour, calming the bees with a few gently puffs of smoke, in preparation for opening the hive – making the whole experience more enjoyable for all involved – also lessening the risk of being stung. The bees are not harmed, and the beekeeper is protected: win-win. If, however, you were a honey bee, you would have two stomachs. Yes, that’s right, and a fairly major point that these vegan propaganda bloggers somehow ‘forget’ to mention. Honey bees have two stomachs. One is the ‘true’ stomach; part of their digestive system. The other is a purpose-specific and much larger ‘honey stomach’. Not a part of the digestive system, but a separate organ entirely, serving as shopping bag, mixing bowl, cooking pot and storage container all in one, where nectar (a sweet sticky liquid collected from flowers) is stored and processed into honey before being packed for storage in the hexagonal comb cells – from where it can later be retrieved as needed. Yes, it is enzymes in the honey stomach that transform the nectar into honey. And yes, the process involves passing the nectar/honey from bee to bee, each taking a turn in the work – but hey, this is bees, not humans. And not ‘vomit’.

If, however, you were a honey bee, you would have two stomachs. Yes, that’s right, and a fairly major point that these vegan propaganda bloggers somehow ‘forget’ to mention. Honey bees have two stomachs. One is the ‘true’ stomach; part of their digestive system. The other is a purpose-specific and much larger ‘honey stomach’. Not a part of the digestive system, but a separate organ entirely, serving as shopping bag, mixing bowl, cooking pot and storage container all in one, where nectar (a sweet sticky liquid collected from flowers) is stored and processed into honey before being packed for storage in the hexagonal comb cells – from where it can later be retrieved as needed. Yes, it is enzymes in the honey stomach that transform the nectar into honey. And yes, the process involves passing the nectar/honey from bee to bee, each taking a turn in the work – but hey, this is bees, not humans. And not ‘vomit’. Bees need two main foods to survive, and both are collected from flowers; protein (in the form of pollen) and carbohydrate (in the form of sugar). Honey is 82% sugar, but it also contains trace vitamins and minerals and mystery substances that science is unable to identify or replicate. It really is magical stuff, and as a responsible beekeeper putting the welfare of my bees before my own sweet tooth, I personally choose to leave sufficient honey on the hive for the bees, taking only the surplus – if there is a surplus – for human use. But of course, not everyone does it this way, and again it is commercial beekeepers who are most guilty of ‘stealing’ the entire honey harvest from bees that they may then destroy – or, if they do keep them going overwinter, feed on sugar as the cheaper alternative. The beekeeping community is strongly divided over whether this does – or does not – harm the bees health. I personally feel that it’s a bit of a ‘no brainer’. Bees invest their entire life in making this special food, on which they rely for survival. I myself believe that replacing this purpose-created food with processed white sugar has got to have a negative impact on bee health. It is a fact, however, that all beekeepers will at some point rely on sugar as a means of ensuring their bees have enough to eat in times of shortage. Bad weather, extreme cold, attack by predators, disease and other disasters can leave a colony short of food; as can an increase in brood (baby bee) production; and the only way to overcome this is to provide additional sustenance, in the form of sugar as carbohydrate. This is done by giving

Bees need two main foods to survive, and both are collected from flowers; protein (in the form of pollen) and carbohydrate (in the form of sugar). Honey is 82% sugar, but it also contains trace vitamins and minerals and mystery substances that science is unable to identify or replicate. It really is magical stuff, and as a responsible beekeeper putting the welfare of my bees before my own sweet tooth, I personally choose to leave sufficient honey on the hive for the bees, taking only the surplus – if there is a surplus – for human use. But of course, not everyone does it this way, and again it is commercial beekeepers who are most guilty of ‘stealing’ the entire honey harvest from bees that they may then destroy – or, if they do keep them going overwinter, feed on sugar as the cheaper alternative. The beekeeping community is strongly divided over whether this does – or does not – harm the bees health. I personally feel that it’s a bit of a ‘no brainer’. Bees invest their entire life in making this special food, on which they rely for survival. I myself believe that replacing this purpose-created food with processed white sugar has got to have a negative impact on bee health. It is a fact, however, that all beekeepers will at some point rely on sugar as a means of ensuring their bees have enough to eat in times of shortage. Bad weather, extreme cold, attack by predators, disease and other disasters can leave a colony short of food; as can an increase in brood (baby bee) production; and the only way to overcome this is to provide additional sustenance, in the form of sugar as carbohydrate. This is done by giving  These diseases spread from bee to bee, and from colony to colony, through the normal social contact of bees going about their normal bee activity – unknowingly passing virus, bacteria, fungus, moulds and parasites between themselves and each other. As beekeepers we regularly inspect our hives for signs of these problems, and take the appropriate action to prevent or treat. Wild bees simply die from these same diseases, or at best struggle against adversity – in the meantime spreading the infections far and wide, free from human ‘interference’. From this perspective, domestic beekeeping plays a vital role in supporting honey bees to survive and thrive; beekeepers striving to protect and strengthen bee colonies against disease. Again, this is more true of small-scale beekeepers, rather than those working on an industrial scale; for as hobbyists and small-scale producers we take care to protect and maintain the health of our bees – whereas larger scale operators may be more inclined to miss the signs, with such vast populations to monitor, and may prefer to destroy rather than treat, if disease is present. They also work within a much more generous financial margin; the loss of one hive countered by the profits of another. Whereas small independent beekeepers will be working within a much tighter financial framework, reaping smaller monetary rewards whilst very likely paying out more in higher quality bee care. So, not eating honey will not ‘save’ the bees and could in fact have the total opposite effect; forcing the more responsible and environmentally aware beekeeper out of action, thus reducing the total bee population, with the resultant drop in monitoring and treatment leaving bee disease free to spread more freely.